Fluff celebrated by many, but it’s only made in one place

By David Liscio

When talk turns to Marshmallow Fluff, it’s not unusual to hear enthusiastic opinions from pre-teens, Baby Boomers and those enjoying their golden years.

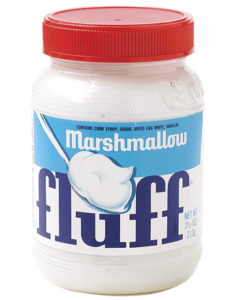

After all, the beloved white goop has been around for decades, with nearly every ounce produced at the Durkee Mower factory in Lynn.

In fact, Fluff has a birthday coming up. The popular sugary sandwich spread turns 100 years old in 2017 and fans contend it’s a reason to celebrate.

In fact, Fluff has a birthday coming up. The popular sugary sandwich spread turns 100 years old in 2017 and fans contend it’s a reason to celebrate.

Oddly enough, the annual Fluff Festival is held in Somerville, which boasts a connection to the product, but isn’t host to where it’s made. That distinction is solely Lynn’s—and don’t let anyone from Somerville tell you otherwise.

To emphasize that point, five years ago, the Lynn Museum & Historical Society began selling limited-edition t-shirts with the words: “I’m a Fluffernutter. I’m from Lynn.” The current leaders of Durkee-Mower were generous in offering the rights to use the Fluff brand logo along with the Fluffernutter logo. Sales of the t-shirt not only helped to raise money for educational programs at the museum, but helped to reaffirm Lynn’s title as City of Fluff.

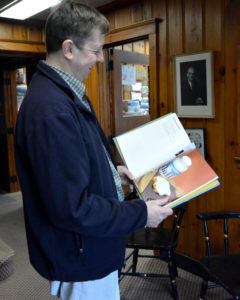

Vintage jars of Fluff on display at Durkee-Mower’s Lynn headquarters.

So how did a festival wind up in any city other than Lynn? As it turns out, Somerville’s efforts to rehabilitate its crumbling Union Square neighborhood called for not only shoring up the commercial buildings and housing stock, but finding ways to attract visitors. Eleven years ago, event organizers joined forces with the redevelopment team to sponsor the festival in Union Square.

The madcap one-day event, which typically attracts between 15,000 and 20,000 visitors, features a Fluff jousting match, Fluff sandwich-eating antics, Fluff train, Fluff cooking contest, scavenger hunt and other wild and whacky activities. Ironically, the Fluff itself is shipped in from Lynn.

Fluff was chosen—some might even stay stolen—because its origins can be traced back to 1917, when Somerville resident Archibald Query began making the concoction in his kitchen and selling it door to door. But, the Somerville connection to Fluff began and ended in Query’s kitchen. In fact, it wasn’t even called Fluff until businessmen H. Allen Durkee and Fred L. Mower named it that after buying the formula from Query in 1920 for $500. By that time, Query had shut down his small operation because World War I had created shortages of sugar and other ingredients.

Durkee and Mower, both graduates of Swampscott High, were already involved in a candy-making venture, started upon their return from the battlefields of France where they served in the U.S. Army infantry. So they continued to cook their confections at night and sell door-to-door during the day. At the time, a gallon container of Marshmallow Fluff sold for a dollar.

It didn’t take long for grocers to realize customers wanted to buy the product off the shelf instead of directly from a salesman. Fluff had established a glowing reputation among local mothers who quickly amassed and shared their recipes. Many praised the fact that Marshmallow Fluff does not require refrigeration.

A delicious Fluffernutter sandwich.

By 1929, Durkee and Mower had outgrown their small facility and moved to a factory on Brookline Street in East Lynn, tripling their floor space to 10,000 square feet. Four more employees were hired, bringing the staff to 10. The company also produced an instant cocoa. The following year, they began advertising on the radio, sponsoring the weekly “Flufferettes” talk show that was broadcast throughout New England. The show featured live music, comedy skits and commentary. It aired for over a dozen years.

Durkee-Mower bought a two-story building in Lynn during the Great Depression of the 1930s and, at the close of World War II in 1945, built a modern office building adjacent to the factory. The current factory opened in 1950 and has been churning out the sticky spread at record rates ever since, ensuring that Lynn stays on the map as the official home of Marshmallow Fluff, no matter whether other communities choose to claim part of the fame.

These days, Durkee-Mower is headed by Don Durkee and Jon Durkee, the son and grandson of founder H. Allen Durkee. Don, 91, is in semi-retirement, but still holds the title of president. Jon serves as treasurer and executive vice president.

Jon Durkee, grandson of founder H. Allen Durker, serves as treasurer and executive vice president of the company.

“We’re happy to keep the legacy going,” said Jon. “I’d say we’re caretakers of the product, which has become so iconic over the last 100 years. God willing, it’ll be around for another 100 years.”

The company produces about seven million pounds of Marshmallow Fluff per year, sold mainly in pint-to-quart-sized plastic white tubs. New technology has improved the way the company manages its accounting, but not necessarily production.

“Most of our machines are 60 years old,” said Jon. “Even the new mixers we bought last year are virtually the same as the 50-year-old ones we replaced. It’s almost like a time machine.”

In addition to its iconic white Fluff, the company also makes a strawberry version, as well as a beet-dyed batch that’s primarily for its European customers, a raspberry-flavored version for its Canadian market and a chocolate version for German consumers. And of course, the peanut butter and marshmallow combination of the Fluffernutter remains a popular childhood (and adulthood) staple.

Interestingly, the Fluffernutter was the brainchild of Emma Curtis of Melrose, who was Revolutionary War hero Paul Revere’s great-great-great granddaughter. According to the New England Historical Society, Emma and her younger brother, Amory Curtis, began making and marketing Snowflake Marshmallow Crème (an early competitor from 1913 to 1940). The Curtis siblings didn’t invent the spread, but they popularized it for home use. Emma created new recipes that were printed on product brochures and labels, and she promoted them on a weekly radio show and in a newspaper column. Her fluffernutter recipe was unveiled during World War I and dubbed the “Liberty Sandwich.” Today, however, the Flutternutter is a registered trademark of Durkee-Mower Inc., taking its rightful place at home in Lynn.