By DAVID LISCIO

A national initiative to transform abandoned railroads into public bicycle and walking trails is stirring controversy in at least two North Shore communities.

Lynnfield and Swampscott residents remain divided, but recent ballot votes in both communities favored trail construction and authorized partial funding.

Those who embrace the Rails to Trails concept contend such paths enhance abutting property values, create healthy recreational opportunities and put the land to better use.

Detractors are concerned the trails will bring noise and traffic, encourage a parade of strangers through their neighborhoods, increase local taxes to pay for maintenance, damage environmentally-sensitive areas and lead to crime.

Bicyclists, pedestrians and runners of Motorized vehicles are prohibited.

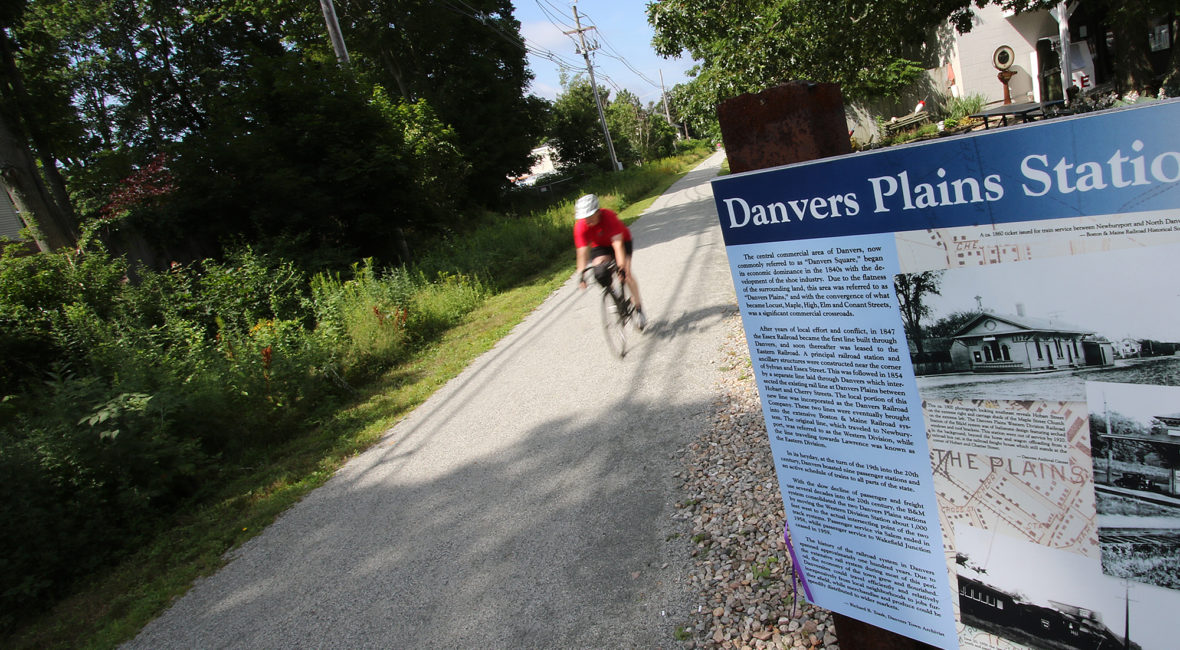

Several local communities have successfully built trails at little cost to taxpayers and no discernible spike in crime. Danvers, Marblehead, Peabody, Revere and Saugus all have some form of bicycle/ pedestrian trail and few problems have arisen.

The Rails to Trails initiative encountered stumbling blocks in Swampscott and Lynnfield, although the respective boards of selectmen and voters in both communities subsequently authorized bicycle and pedestrian trail projects.

LYNNFIELD

In Lynnfield, voters on April 24 authorized the town to move forward with plans for a 4.4-mile Wakefield/Lynnfield Rail Trail that begins at the Galvin Middle School on Main Street in Wakefield and extends to the Lynnfield/Peabody town line.

Those opposed to the project, like Citizens of Lynnfield Against the Rail Trail, contend it’s a mistake and plan to challenge the vote outcome.

The project mustered strong community support and will be funded by $7 million in state and federal grants. Friends of the Lynnfield Rail Trail will raise $5,000 annually for trail maintenance.

Lynnfield resident Thomas Grilk, CEO of the Boston Athletic Association and the Boston Marathon, posted a personal statement on the Friends group website, www.lynnfieldrailtrail.org, that outlines the benefits of a fitness trail. As Grilk put it, “Whether as nearby as Peabody or Lexington, or in more distant locales such as New Hampshire, Michigan, California, Germany or countries in Asia, I have yet to see a fitness trail that did not become a treasured asset of the communities privileged to be served by it. I welcome it to my backyard.”

Vince Inglese, a member of the Friends’ group Leadership Team, said the funding meets the state Department of Transportation estimate. “The trail cost is between $7 million and $9 million. Lynnfield’s trail will not be surfaced with stone dust. It will be paved with asphalt and be ADA (Americans With Disabilities Act) compliant,” he said.

Inglese said the $5,000 in annual trail maintenance amounts to $2,000 per mile and is modeled after successful trails in Topsfield and Danvers where support groups are composed of volunteers, as it would be in Lynnfield. He noted those communities raise maintenance funds through sponsors of one-tenth-mile trail markers.

“The marker would have the donor’s or the business sponsor’s name on it,” he said.

Not every Lynnfield resident was pleased by the pro-trail vote.

Robert Breslow posts statements on the opposition group’s website www.noforlynnfield.com.

After the April vote, he announced the group plans to continue its fight, adding that any structure built in Lynnfield Conservation Commission.

Breslow also pointed out any potential grants for the project likely would not be made available from the state or federal government until 2021.

The opposition group has warned Lynnfield taxpayers they could be responsible for construction budget gaps, extra policing and emergency medical response costs, fence maintenance, storm damage repairs and additional parking expenses, all without any guarantee of future funding.

Breslow decried the trail will increase town traffic, put more bicyclists on the roads, create a need for traffic lights, heighten the risk of fire and crime, cause noise and water pollution, result in litter and dog waste, and present a threat to the environment.

Lynnfield and Wakefield in 2007 conducted a joint feasibility study on whether to build the bike path along property owned by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA). The corridor was once part of the southern section of the now defunct Newburyport Railroad. The subsequent plan showed 1.9 miles of trail in Wakefield and 2.5 miles in Lynnfield. Once built, it would become part of a 30-mile trail plan linking eight Essex County communities.

Reedy Meadow has also complicated Lynnfield’s efforts to create a bike trail.

The meadow was once a marsh and during storms it still floods the railroad tracks that cross it. The flooding has clogged culverts beneath the rail bed, curtailing the flow of water.

The situation has raised questions about potential environmental damage, and the cost of building and maintaining a wooden walkway across the wetlands.

Wakefield residents have expressed concern about the lack of parking for trail users, particularly near the town’s already-congested business district. Two additional parking areas on town-owned land have been examined as solutions.

SWAMPSCOTT

In Swampscott, a measure to spend $850,000 on design, engineering and the legal costs of acquiring property rights to the proposed trail, was passed by Town Meeting on May 15. The vote was 210-56.

The outcome was quickly challenged by a citizens’ petition that gathered enough signatures to put the appropriation to a ballot vote on June 29. Forty-six percent of Swampscott voters turned out, resulting in an outcome of 2,741 to 2,152 in favor of the trail project.

“I’m very happy that plans for a rail trail will move forward,” said Naomi Dreeben, chairwoman of the Swampscott Board of Selectmen. “Now it’s time to heal the rift in our town.”

In addition to trail-related concerns voiced by other communities facing similar decisions, Swampscott residents must still address controversy over land ownership along the former rail corridor.

The Boston & Maine Railroad once operated trains along the route. When the company divested, the land was sold to the Massachusetts Electric Co., now known as National Grid. The electric company utility poles were installed along the right-of-way and remain in place to transmit kilowatts to Marblehead.

Over the years, the steel rails and wooden railroad ties were removed, and some abutting residential property owners began using pieces of the National Grid land as their own. A few of those abutters attempted, and in some cases may have succeeded, in obtaining title to those plots.

“If certain residents encroached on land owned by National Grid, that means they have been using it and might not be paying taxes on it,” said Swampscott Community Development Director Peter Kane. “We’re not looking to take anyone’s land. We simply want an easement. We can’t go forward with any grant application until we have the acquisition rights in hand.”

Of the $850,000 approved by Town Meeting, $610,000 will be used to acquire the land-use rights. The remainder would cover design and planning costs.

If a property title search indicates an owner has encroached on the National Grid land, it would be difficult to challenge the town’s intent to obtain an easement. However, if the property owner holds title to an abutting piece of the utility corridor, the town would be forced to take legal steps.

Kane acknowledged the ownership borders are murky along a small section of the rail corridor, adding,

“This isn’t an eminent domain taking. We just need to clarify ownership through title searches.”

Kane’s office will now solicit bids for design and engineering plans. The annual debt service on $850,000 is approximately $65,000, he said.

The proposed 10-foot-wide trail would follow a route from the Swampscott train station to the Clarke Elementary School, Swampscott Middle School and Stanley Elementary School until it connects to Marblehead’s trail.

“The plan is for a stone dust surface, which would be aesthetically in keeping with Marblehead’s and much less costly than an asphalt surface,” Kane said.

At slightly less than two miles in length, trail construction would cost approximately $400,000, but that estimate is not definitive nor is it included in the funds approved by Town Meeting, he said.

Kimberly Nassar, who headed the opposition group, said in a statement following the June 29 vote, “We will now continue the legal steps needed to demonstrate what we have stated all along: that the abutters own much of the land along the proposed rail trail and for the town to acquire that land by eminent domain will require millions of dollars in taxpayer monies.”

As for other concerns unrelated to the land titles, Kane said, “They’re pretty much the same wherever somebody proposes building a trail. It’s fear of the unknown, fear of change. I read a newspaper story that quoted a Danvers resident who was very much opposed to the Danvers trail but now uses it regularly and can’t say enough good about it.”

Lynn

In Lynn, the plan for a bike and pedestrian trail has been under discussion for years. Bike to the Sea has been part of those talks, which involve obtaining a necessary right-of-way.

“You must sign an agreement with the property owner that says you will take care of the right-of-way. That just hasn’t happened in Lynn,” said Attorney Stephen Winslow of Malden, founder of Bike to the Sea, an organization that over the past two decades has actively supported bike trail initiatives.

In some communities, that agreement may mean accepting responsibility for routinely clearing brush, maintaining pathways and elevated walkways, and even plowing snow in winter if the trail surface is asphalt.

“If the trail becomes an integral part of the community, where it provides a walking route to the schools or the local businesses, then it might be kept open year round,” Winslow said.

According to Lynn Community Development Director James Marsh the city’s trail project is currently in the pre-design phase. If built, it would extend 1.2 miles through Lynn along a former MBTA railroad corridor, starting where Boston Street crosses the Saugus River and ending on Spencer Street.

“Before we jump into it, we want to know all the variables that are associated with liabilities,” Marsh said. “That’s why we’re taking baby steps. Those are important if we’re going to make this a reality.”

Marsh estimated the design would cost $50,000 to $75,000, 50 percent of which would be paid for by a grant from the Lawrence and Lillian Solomon Foundation.

The foundation strives to increase access to the state’s natural, cultural and recreational resources and recently assisted the Watertown Riverfront Park and Braille Trail.

Marsh, representatives of the Office of the Mayor, and local property management executive Gordon R. Hall have been overseeing the plan, which includes discussion of a long-term land lease from the MBTA, Marsh said.

Lynn officials also have been monitoring the waterfront along the Lynnway where new development is slated because any construction would impact the proposed pedestrian boardwalk connecting the Nahant traffic circle to the General Edwards Bridge.

Marsh cited the former Beacon Chevrolet property across from North Shore Community College and the O’Donnell property near the Saugus River as waterfront development sites. “Under Chapter 91, a boardwalk would be required at each site and the private developers would pay for it,” he said.

“But all of that is many years away,” he said.

STATEWIDE

Richard Fries, executive director of MassBike, said Massachusetts has the potential to become a world leader in bicycle trails. “We’re sitting on a network that could turn us into the Netherlands of America,” he said.

According to Fries, when Americans discuss bicycling, talk turns to places like San Francisco, Denver, Portland and Minneapolis. “The Northeast, however, has this amazing labyrinth of transportation corridors hidden in plain view. Rail beds, both active and abandoned, are just the start. Canals, aqueducts and power lines are another layer of under-utilized corridors. Riverfronts are another critical component to the rebirth of cities, big and small,” he said.

BUILD IT AND PEOPLE WILL COME

Dan Tieger of Manchester-by-the-Sea, founder of the North Shore Bikeways Coalition and visionary behind the Border to Boston concept in the 1990s, continues to personally enjoy regional bike paths while he monitors fitness trail initiatives nationwide. He commutes daily to his job as a scientist in Gloucester.

“Border to Boston was founded in 1994. The trail evolved from the New Hampshire border down to Danvers, but since then people have pushed it south to Peabody. It took twenty-something years,” he said. “And other trails may eventually connect to it.”

Tieger jokes about the scars he and Winslow received from opposition groups over the years.

“Some communities say they don’t want a trail, but once they have one, there’s no turning back,” he said, recalling Palm Beach, Fla., where wealthy abutters erected tall fences to keep out trail users. But once the trail began to flourish, those same residents cut doors in their fences through which they could gain access from their houses.”

“These trails are actually linear parks,” he said. “You’ll see people walking dogs, kids being pushed in strollers, people on bicycles or rollerblades. It becomes an enjoyable place; instead of having a decrepit ex-railroad where people go to drink it becomes a clean, healthy area.”

(David Liscio is a North Shore-based photojournalist, www.davidliscio.com.)